My favorite RPG rules are written in naturalistic language.

What do I mean by this? Well, the easier it is to speak in-character about an effect, status, or ability, the more naturalistic the game's language.

Not Naturalistic: I have 1,000 experience points. I am level 1.

More Naturalistic: I have 1,000 gold. I am a veteran.

The concept of experience points and levels probably doesn't exist inside the player character's mind, whereas gold and class titles do. The less a player has to double-think between the fictional universe and the game mechanics, the smoother and more enjoyable I find the experience. The more that a player character says exactly what the player would say, the happier I am.

This isn't just a criticism of dissociated mechanics like experience points and levels, though. Sometimes rules are written with so many clauses and sub-clauses, trying to prevent possible misuse or misinterpretation, that they become a complicated legalese. Sometimes rules are written in a "secret code" that takes up less space on a page but is nonsense to the uninitiated. When rules are written in a baroque way they work against their own clarity.

(This is one of my most crucial critiques of 5E. The language of the rules seems to be written in such a way that it is trying to avoid the most diabolic interpretation.)

|

| Get this shit out of my rulebooks |

So how do we move the needle from non-natural to natural-language rules?

Diegetic names for abilities

Bad: My character has a feat called "BFG," which lets them have a gun that does 6d6 damage.

Better: I'm packing a Yamaha Raiden assault rival.

In a game like D&D, spell names are diegetic. That is, they exist inside the fictional universe. A character casting magic missile might say, "I'm casting magic missile," and everyone versed in arcana would say, "Yes, that is the spell we call magic missile." By contrast, feat names are not diegetic. If Drizzt shows up with two scimitars, someone wouldn't say, "Ah, he has dual wielder" in character. You might say Drizzt is a dual wielder, or knows how to dual wield, but the names "Dual Wielder," "Elemental Adept," or "Tavern Brawler" are not in-universe terms. I mean, hell, in D&D even class names might not be diegetic. If someone is a monk, would you call them a monk, or do those monk levels just represent them being agile or a bar-room brawler?

Natural language rules provide diegetic names for character traits.

- Consider making your class your actual job. A bard is a graduate of the College of Bards, having been trained to harmonize with the Ainulindalë and re-sing parts of the world. A fighter is a knight given the hereditary rights to demand a Trial by Arms and to wear armor.

- Give all maneuvers or abilities diegetic names. Give them a history. Instead of "Displacing attack," consider "Tenkar's Bullrush," which is a specific martial technique developed by Tenkar during the Orc and Goblin War of Year 1001.

- Tie traits to life events and in-universe places. If you can change the elements of your spells, perhaps you were "Born Under the Sign of the Wheel." If you can ride large creatures, perhaps you were trained by the "Dragon-riders of Qarth."

Avoid abstract mechanics

Bad: I lost 3 HP. On the classic scale of 1-22, I am 19 healthy.

Better: I am Injured by the serpent's bite.

If you whisper the word "hit points" on an RPG forum, someone trips over themselves rushing to type the following: "HITPOINTS DONT ACTUALLY SIMULATE REAL DAMAGE ITS LIKE LUCK AND EXHAUSTION FROM A BATTLE READ THE BOOK ACTUALLY FOEGYG"

OK so sometimes hit points are abstract. An arrow to the face would kill you, but taking the maximum amount of an arrow's damage won't, so getting shot with an arrow and suffering the max of 6 damage is only being grazed by the arrow. But then what does the spell Heal do? Why is it called Heal if it just refreshes your luck? What if you fall and take 12 falling damage? Are you just getting, like, tired by hitting ground? And what if you're playing a game where a human can gain 100 hit points and survive 1,000 foot falls?

The conversation around what hit points represent is this Gordian knot of abstract mechanics. 6 damage represents a significant wound, enough to kill a normal person but probably won't kill a trained fighter. 1,000 experience points represents an a-ha moment for an untrained person but is obvious to master of the craft. Joey has 10 Strength and is weaker than Tammy who has 15 Strength. You can't use the terminology "hit points" or "experience points," and you wouldn't say "Tammy is about 15 out of 20 Strong" but your character understands what these abstract mechanics represent.

Natural-language rules avoid abstract mechanics in favor of more concrete one-to-one representations of the fictional world.

- Consider making abstract mechanics more concrete. A wizard doesn't have 6 mana, they have "six bound daemons, each of which may be commanded to perform a single spell."

- Consider defining what certain game procedures mean in the fiction. For a dice pool system, every dice rolled is a single swing of the sword. Every red defense dice rolled is a piece of armor. Every black defense dice rolled is your character dodging out of the way.

In-character language for abstract mechanics

Bad: When a dragon has lost 50% of their total hit points, they can use their breath ability twice per turn.

Better: When a dragon is bloodied, they can use their breath ability twice per turn.

OK, so some rules are abstract. There's nothing wrong with that. But the more in-character language you have to talk about them, the better. This lets you describe the flow of the rules in in-character terms.

Natural language ties abstracted mechanics to the fiction they're simulating.

- Choose flavorful terms for game concepts. Instead of saying "dungeon turn," consider a word like "watch." It's easy to say "I only have the strength to cast one spell per watch." A "first level spell" might be a "spell of the first rune."

- Consider providing in-character terms for milestones that are referenced frequently. If you can deal either 1 or 5 damage, you can call 1 damage "a hit" and call 5 damage "a critical hit." Have a list of class titles. A 1st level fighter is a veteran, a 5th level fighter is a lord.

Use associated mechanics

Bad: I can cast a spell once per encounter.

Better: I can cast a spell once before I must rest and pray to my god.

Even better: The limits of this magic allow me to cast it only once before the sun next crosses the horizon. Once the sun sets, I can cast it once more. And then again once the sun rises.

"An associated mechanic is one which has a connection to the game world. A dissociated mechanic is one which is disconnected from the game world."

In Exalted, there is the concept of scenes. A magical effect might last for the rest of the scene, whether it's two rounds or two hours of fiddly combat. This adds to the narrative, cinematic flow of the game.

In Gubat Banwa, gameplay uses a grid. A enemy combatant might be six squares away, but your effect only targets someone within a range of three squares.

Terms like scenes and squares facilitate easy play at the table but can be fiddly to transform into in-character concepts. Not impossible, just requires some double-think.

Natural language rules use in-universe times, distances, and restrictions.

- Tie game concepts to fictional space. If a square is 5 ft., consider using distances instead. If a dungeon turn is 10 minutes, consider using time.

- Provide in-character justification for narrative abstractions. If spells only last until the end of battle, you can explain the physics of magic being tied to the ebb and flow of mana. Magic isn't science. Spells might last a minute or ten minutes or all day.

- Discover unique ways to challenge characters by drawing these diegetic limitations to their natural conclusions. If a spell can only be cast once a day, why? Is it tied to the mana of the sun? Can some spells be cast only once a month? Once a year?

Human-readable crunch

"But wait! I like crunchy games! This is all well and good if you wanna play FKR or something, but leave my feat trees alone."

Oh gentle reader, I don’t think anything here precludes crunch! But I think there's a path to a better crunch - a human readable crunch instead of crunch that feels like a punchcard for a steam-powered computer.

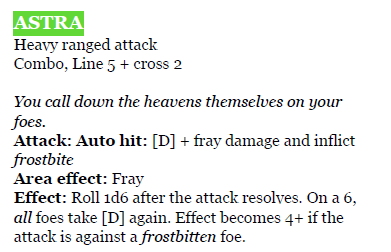

Here, take these two examples from Gubat Banwa and Lancer. Both 4E inspired, grid-based, build-a-thon slugfests. But one rule block feels like it's written as example code in a Khan Academy tutorial and one feels like you're explaining what happens in the game's fiction.

Bad:

Better:

Natural language explains mechanics in a way that makes sense to normal people.

Fewer numbers

Bad: I have a +2 to Survival. I’m pretty good at survival.

Better: I am Trained in Survival.

Numbers are a sticky wicket. They are definitely human readable but they are difficult to talk about in-character.

|

| Fate allows you to say your skill's adjective instead of the number |

Fate attempted to provide adjectives for their skill ranks, which is admirable, but I can never remember if +4 is Good or Fair or Superb or... It is just easier to say "I have a +4 Survival" than to say "I am Great at Survival."

Let me give 5E some credit here. "Advantage" and "disadvantage" is simpler to calculate and more naturalistic language than calculating infinite +1s from different bonus sources (proficiency, magic, shield, feat, item, ad nauseum). Proficiency is another good gloss of having in-character language to describe a numerical bonus.

Natural language rules use fewer numbers and rely less on math.

- A +1 sword is a boring magic item. You factor it into your attack bonus and forget it. It hardly feels magical. A sword that is invulnerable is more memorable and relies less on numbers. Use the sword to prop open a closing gate, hold open a dragon's mouth, fish something out of an acid lake, etc.

- Consider removing countables. Instead of having 20 HP, you might have each attack = 1 Wound. Each Wound removes something from the character sheet. Instead of having 1 gold = 1 XP, an entire golden hoard might count as "Treasure." Each recovered Treasure allows you to gain a level.

Conclusion

None of this means that I don’t like games with some of these "bad" elements. His Majesty the Worm has more than a few! But a few unnatural-language rules are easier to navigate around than many. My preference lies at the “natural language” side of the sliding scale, and I try to get there in my game design.